A solar simulator’s irradiance is the light power (in Joules per second, or Watts) that shines on a given area, and is usually reported in W/m2 or mW/cm2.

You may have heard that the standard irradiance for sunlight on Earth (the AM1.5G spectrum) is 1000.4 W/m2 (or 100 mW/cm2), while the standard irradiance for extrasolar sunlight (the AM0 spectrum) is 1366 W/m2 (or 136.6 mW/cm2).

These numbers represent the total integrated irradiance of their respective spectra, for wavelengths from 280 nm to 4000 nm. In other words, this irradiance value is the sum of all contributions from a very wide range of the sun’s electromagnetic emissions.

Many applications do not depend on the full 280 nm to 4000 nm range. Monocrystalline silicon solar cells, for example, only respond in the approximate range of 400 nm to 1100 nm. The rest of the spectrum outside this range might contribute to heating (for wavelengths above 1100 nm), or to material degradation (for wavelengths below 400 nm). However, for researchers studying the current-voltage performance of a silicon solar cell, their results do not depend on the total irradiance of the standard spectra.

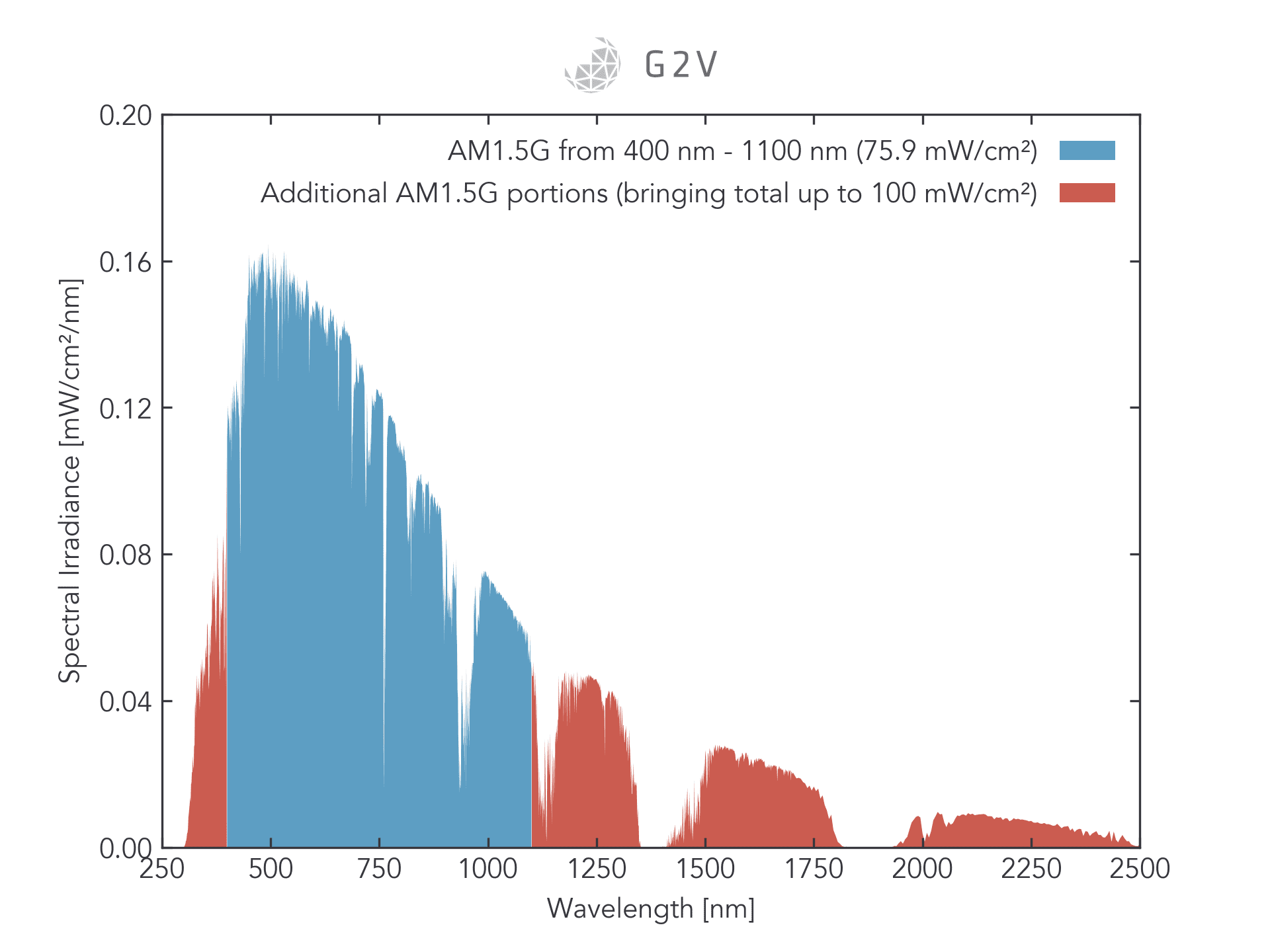

Spectral Irradiance of the Standard AM1.5G Spectrum

For the 400 nm to 1100 nm range, the standard integrated irradiance for AM1.5G is 759 W/m2 (or 75.9 mW/cm2). All of the wavelength portions outside of this range make up the remaining irradiance to bring the total to 100 mW/cm2. This is visualized below.

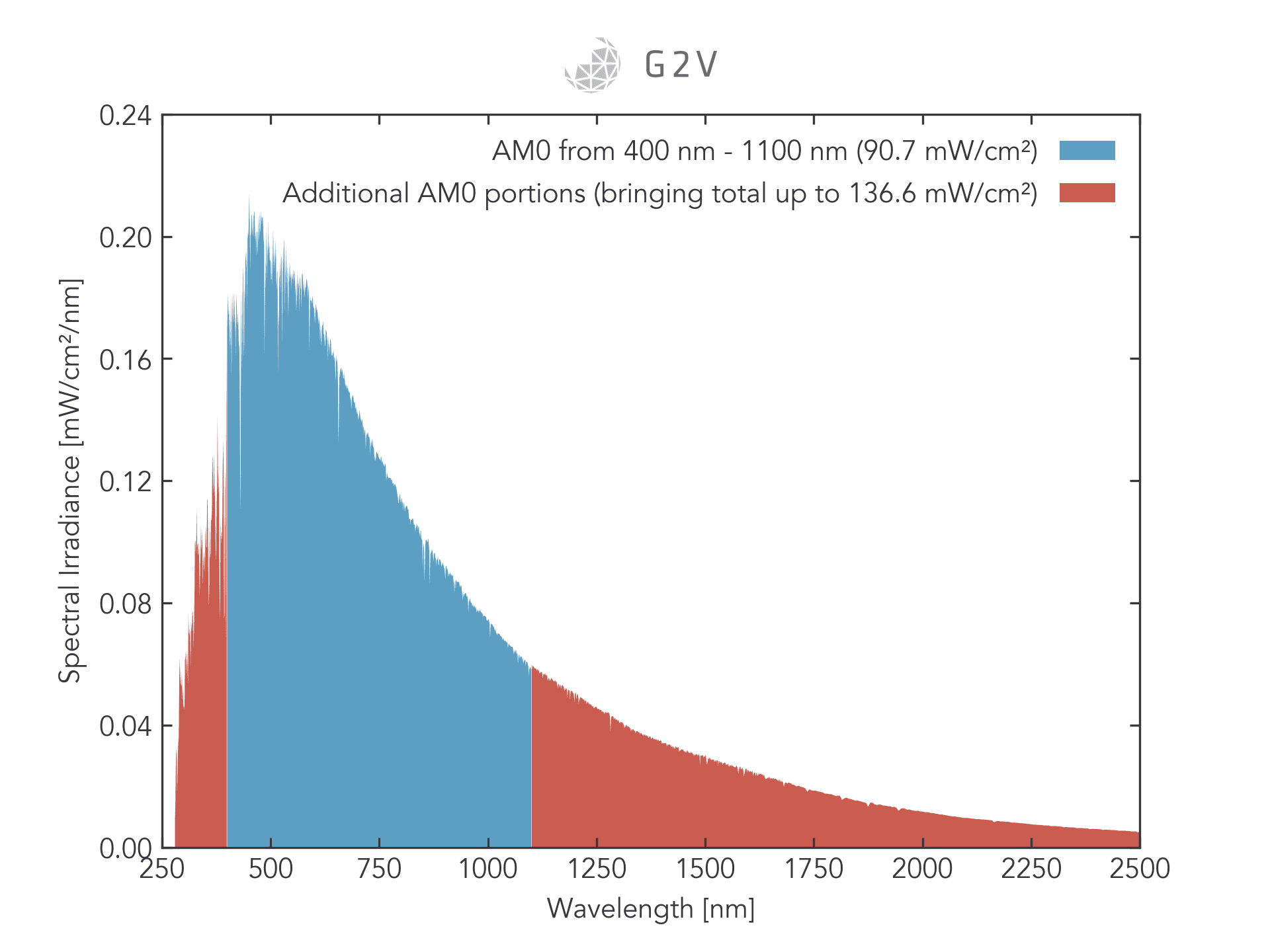

Spectral Irradiance of the Standard Extrasolar AM0 Spectrum

The same is true for AM0 as well. The standard integrated irradiance for AM0 is 907W/m2 (or 90.7 mW/cm2). All of the wavelength portions outside of this range make up the remaining irradiance to bring the total to 136.6 mW/cm2. This is visualized below.

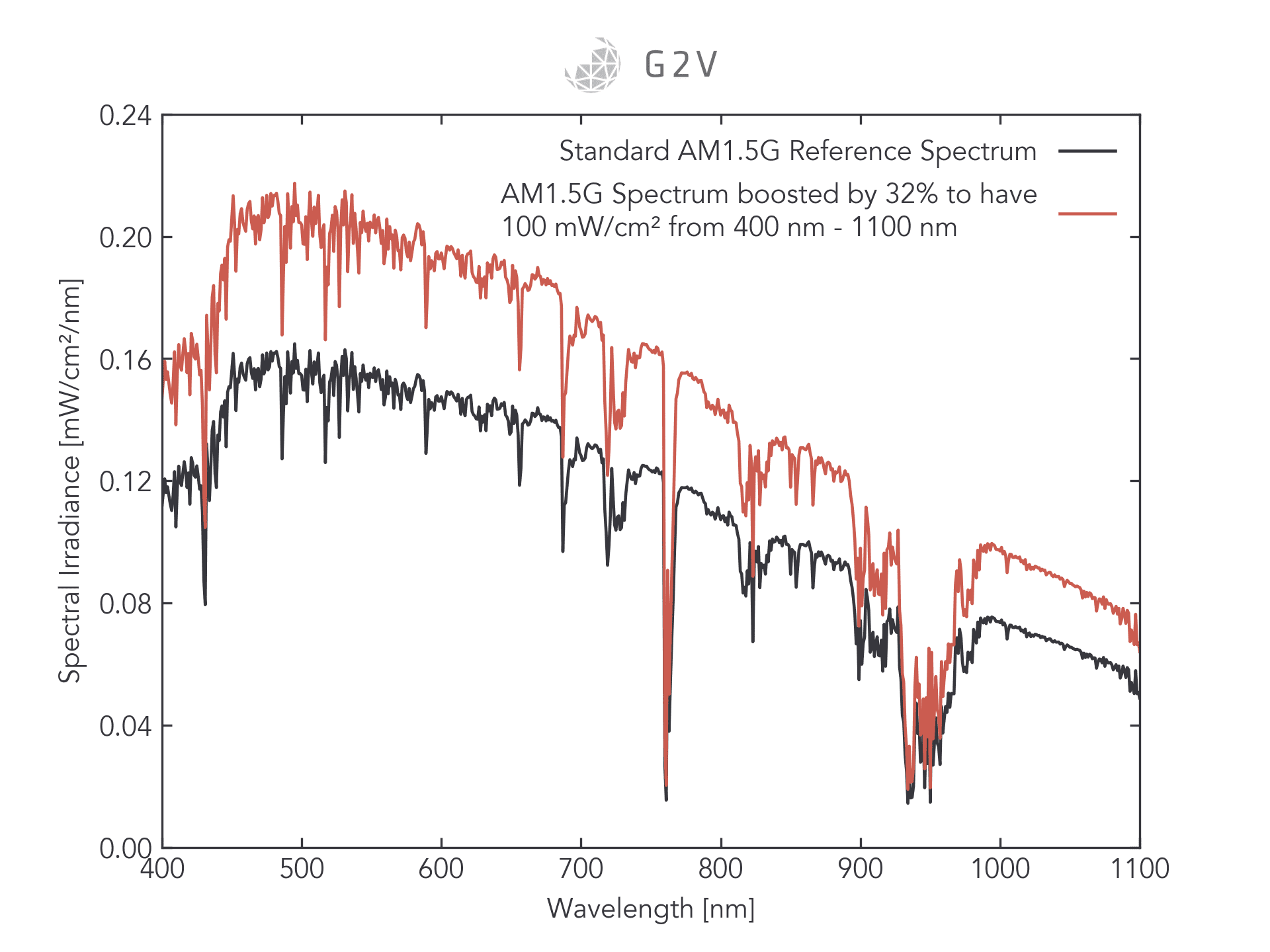

Why is a Solar Simulator’s Calibrated AM1.5G Spectral Irradiance Below 1000 W/m2?

When a customer purchases an LED solar simulator for the 400 nm to 1100 nm range, they often ask us why it appears to have a lower irradiance than the 1000 W/m2 standard.

The answer is that we are calibrating according to the irradiance for the specific portions of the spectrum we are generating. If we tuned our 400 nm – 1100 nm solar simulator to produce 1000 W/m2, we would be outputting an intensity across this range 32% higher than the standard! The figure below visually emphasizes how incorrect this approach would be.

When Reference Solar Cells Are Confused With Power Meters

Where things get particularly confusing is when a silicon reference cell is quoted as having a given response under the standard 100 mW/cm2 (1000 W/m2) sunlight. The reason this is confusing is because, as stated above, standard monocrystalline silicon solar cells only respond approximately in the 400 nm to 1100 nm range.

Therefore, there is no way such a reference cell can give any measure of the solar spectrum outside this range.

If you illuminated it with the appropriately-balanced spectrum with 75.9 mW/cm2 irradiance over the 400 nm to 1100 nm range, and then illuminated it with 100 mW/cm2 irradiance from the full 280 nm to 4000 nm range, you would measure the same output current from the reference cell. The silicon reference cell is mostly blind to the spectrum below 400 nm and above 1100 nm.

In the industry the term “1000 W/m2” is often used synonymously with “standard sunlight”, without understanding the above-mentioned wavelength ranges and spectral balance. Because of this misused naming convention, silicon reference cells are sometimes mistaken as power meters. For many reasons beyond the ones stated above, they are not.

If you measure an LED solar simulator with a true power meter, i.e. one that will report the power contributions of all (or nearly all) wavelengths such as a thermopile, then you will indeed measure the above-mentioned 30% difference between 75.9 mW/cm2 for a 400 nm – 1100 nm solar simulator and 100 mW/cm2 for full-spectrum sunlight.

Understand Your Application’s Spectral Sensitivity

At the end of the day, what’s most important to understand is the wavelength sensitivity of the phenomena under investigation.

If you’re using a solar simulator to study silicon solar cells, then, as discussed, you won’t be able to tell the difference between a solar simulator that emits 75.9 mW/cm2 from 400 nm – 1100 nm and one that emits 100 mW/cm2 from 280 nm – 4000 nm.

If, however, you’re studying multi-junction solar cells that extend out to 1500 nm, you’ll want to make sure your solar simulator produces light out to that region. However, even going out to 1500 nm doesn’t raise the total irradiance to 100 mW/cm2, so insisting on this target irradiance can be quite misleading.

If you are investigating a physical phenomenon that does depend on interactions across the entire 280 nm to 4000 nm wavelength range, then yes, you will certainly need a solar simulator that produces 100 mW/cm2. However, in our experience there are few physical phenomena that depend so broadly on electromagnetic radiation.

If you’re studying material degradation whose mechanisms are primarily in the UV, there is little benefit to having a solar simulator that produces light at 1800 nm, because the latter will likely only result in a changed temperature. It is much more important to have the correctly balanced spectrum in the regions of interest.

LED Solar Simulators vs Traditional Bulb-Based Solar Simulators

The reason the concepts discussed above are relatively new to most solar simulator users is because of the way LED solar simulators are constructed. In contrast to traditional bulb-based solar simulators such as xenon arc or metal halide, LED solar simulators are built by combining several distinct sources of different wavelengths. If a portion of the spectrum is not needed, then that LED isn’t used.

You might think that this puts LEDs at a disadvantage compared to bulb-based solar simulators.

While it’s true that every portion of an LED solar simulator’s spectrum has to be intentionally constructed, this gives much more control and flexibility.

A xenon arc lamp or metal halide solar simulator might produce a broader spectrum, but they have questionable spectral match at higher wavelengths, emitting excess infrared radiation that results in excess heating of samples.

For a more complete discussion and comparison of different solar simulator technologies, please see our comprehensive article here.

The Bottom Line for Calibrated Irradiance

In the end, it all comes back to the wavelength sensitivity of whatever you’re trying to study. Your application’s needs will determine whether you want a full-spectrum solar simulator with a mediocre spectral match across the whole spectral range, or one with exceptional spectral match in key sub-regions of interest.